The

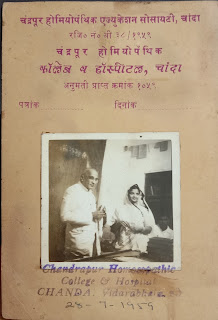

Remarkable Life of Madankunwar Parakh aka Masa’ab

(1919 – 2018)

(Part - 1)

Introduction

Between 1915 and 1947, religion and spirituality

along with nationalism played important roles in developing women’s leadership. Under Mahatma Gandhi spirituality and morality became core values

and the bases for Satyagraha and Sarvodaya. This phase saw the formation

of many women-only organizations that were involved in community work. Since

Gandhiji lived in Wardha for several years, it is only natural that many women leaders in Vidarbha were influenced – directly or indirectly -

by the Gandhian philosophy. One such woman was Madankunwar Parakh of

Chandrapur. Madankunwar Parakh left behind several notebooks and diaries

amongst which the set titled Jeevan Yatra

(The Journey of Life) provides valuable insights into the workings of the

inner processes through which she emerged as a remarkable leader and social worker.

Childhood

Madankunwar Parakh was

born in 1919 to a Marwari Shwetambar Jain family in the house of her maternal

grandfather (nanihal) in a small

tehsil town called Warora in Chandrapur district. Her grandfather Ratanchandji

Kochar was a wealthy businessman who traded in gold and silver and owned 500

acres of agricultural land. Her father Champalalji Baid Mohta and mother Birjibai

lived in Chandrapur and both were extremely religious persons.

When she was around two

years old, her aunt took her to Mungeli in Bilaspur district of Chhatisgarh

where she stayed till the age of seven. Thereafter she returned to Warora and was

admitted to a local school. She proved to be a quick learner and after quickly

completing her lessons she ran out to play games like kho-kho and phugadi. She

was a strong-willed child and even at that tender age fearlessly complained against a teacher

who used to cane the girls.

As a ten-year old, she

attended the sermons (vyakhan) by

wandering Jain Sants and became interested in the lives of great rulers, gods, and saints.

Once in a vyakhan she heard about the

importance of learning the 72 arts for men and 64 arts for women and this left

a deep impact on her. In a way she remained a life-long student, absorbing the many

skills and disciplines needed for leading a good and healthy life. Throughout

her life Masa’ab remained a staunch follower of Jainism – she followed the

rules of ahimsa, vegetarianism and served the Jain Munis and Sadhvis who

came to Chandrapur, entering into discussions with them on spiritual matters.

At a very young age she

learned the basics of Ayurvedic medicine from her grandmother’s dharambhai Raj Vaidya Shivnathji Vaid.

From her father she learned Sanskrit and the recitation of shlokas. After watching a performance of Ram Leela she tried her hand at writing small skits which were performed

by her team of friends. She went to her neighbour to learn astrology (Jyotish Shastra), but since the Panditji

could only teach in Odiya and Bengali she ended up learning the rudiments of

those two languages as well. She learned cycling, horse-riding and playing

musical instruments like harmonium.

Those were the days of

fervent nationalism. Gandhiji’s call for Satyagraha

echoed in every corner of the country. The young Masa’ab learned to spin

the Takali and the Charkha. She stitched tricolour flags

dyed with turmeric and neem leaves and took out rallies with her friends

singing nationlist songs – Jhanda ooncha

rahe hamara. May our flag fly high!

Masa’ab notes in her

diary under an entry titled shrimanto se

nafrat that when she was twelve years old, she developed a hatred for rich men. This was because she observed that such men insult their

wives and women in general. She detested the common practice amongst the rich to bring

courtesans from Banaras to perform dances after the birth of a son. Masa’ab was

so disgusted with the degrading treatment of women that she fervently prayed

that she should never be married into a rich family.

Due to her travels

between Warora and Mungeli, Masa’ab’s education did not go much beyond the

second grade.

Marriage

In 1934 she was married to Rekhchandji Parakh,

who, inspite of her prayers, was a wealthy businessman and agriculturist from

Chandrapur city.

Several years later, in

1949, a lady from another Jain family died leaving behind newborn twins apart

from three older children. The woman’s husband was prepared to give up the

newborns to an orphanage. The Jain community came forward to offer some money

but no one was ready to help the babies. Jethmalji fumed at the hypocrisy of

“the wealthy and ahimsic Jain

community” and finally Masa’ab offered to bring the children home.

Unfortunately, the twins were weak and neither survived. Although many praised

Masa’ab for her kindness, she felt that she had caught a close glimpse of the

ugly side of society.

Another time, a poor

labourer called Vitthu Kunbi brought his newborn child to Jethmalji as his wife

too had died at childbirth. Once again Jethmalji handed over the child to his

daughter-in-law. But this time Masa’ab was aware of a difference in her own

attitude. She shared with her husband in confidence that she had fallen in her

own eyes. Rekhchandji was concerned at her declaration and consoled her gently.

“I had taken care of

the twins who were from the Jain community without a care in the world. But

when I touch this child, I end up washing my hands. Why do I feel this disgust

at this tiny baby?” she said in tears.

As days passed she got involved

with the child and never again did she suffer such feelings towards anybody.

Rajasthani

Mahila Mandal and Sarvodaya Mahila Mandal

This was a time when

Rajasthani women were still in purdah and

rarely active in public life. In order to encourage them Masa’ab and a few

others got together and formed the Rajathani Mahila Mandal in 1949. Yashodhara Bajaj – then a widow in her early twenties – played a very active

role in the organization along with Masa’ab. The Mandal provided a space in

which women of the Rajasthani community came together. They started to read

books and newspapers together and taught each other crafts. Teachers were

invited for sessions on Yoga and healthcare. Hindi was promoted and both

Yashodhara as well as Masa’ab passed Hindi Rashtrabhasha Exams. The Rajasthani

Mahila Mandal was applauded when its members offered to nurse patients during

an eye operation camp organized by the government.

Bal

Seva Mandir

Jethmalji Parakh died in 1956 and Rekhchandji discussed with Masa’ab his desire to start an orphanage in his father’s memory. Masa’ab was overjoyed but she made her husband promise that once the orphanage started, he should never rue the extra responsibility. Soon she started the Bal Seva Mandir in her own home. On the very first day, a Muslim child was brought to her. It crossed her mind that she should convert the child to Jainism and so she wrote to her Guru Shri Anand Rushiji seeking his guidance in the matter. His reply settled the matter once and for all – Madanbai, you have taken up a great task. By learning Ahimsa (non-violence) and through Sanskar (qualities) which you impart, the children are already Jains, and therefore do not allow the thoughts of ‘making’ them Jains create an obstruction to this task.

Shardabai, Masa’ab’s

eldest daughter describes the situation in the Bal Seva Mandir thus:

Masa’ab used to sleep surrounded by tiny

babies in basket cribs arranged around her bed and her whole night was spent in

changing them and feeding them. Those days the servants refused to touch the

babies’ clothes because of caste practices and so Masa’ab herself would sit

with mounds of dirty clothes and diapers and spend hours washing them. Once a

child came who was so weak that the doctor said it would die if it did not get

mother’s milk. That time I was breastfeeding my child. Masa’ab called me and

said – can you please breastfeed this baby too, otherwise it may die? I

breastfed that child for two months. Masa’ab

refused to cook anything in the house which could not be shared with the

children. Make only two types of sweets in Diwali instead of four types – she

would say – but make enough quantity for everyone. I will not make anything

which I cannot share with every child. There were teachers who came to the

house to teach the children. The children would put up plays and we played lots

of games with them.

Masa’ab’s core team that ran the Bal Seva Mandir included her family. Once she noticed that some of the helpers were stealing milk meant for the children. She requested her mother, Birjibai to shift to Dhanraj Bhavan where Bal Seva Mandir was located and help her take care of the children, which she did. Another time she discussed with Rekhchandji that the government sanctioned such small amounts for the Bal Seva Mandir that these did not even cover a fraction of the costs. Rekhchandji suggested that they should run a tiffin service (khanawal) and use the profits to cover the costs.

Meeting

Shamsundarji Shukla and other Stalwarts

Shamsundarji Shukla, a

disciple of Acharya Vinoba Bhave and committed Sarvodaya activist came to visit

Sarvodaya Mahila Mandal. Masa’ab requested him to visit the Bal Seva Mandir and

thereafter personally drove him there. Shuklaji was surprised to see Masa’ab in

her traditional attire confidently driving the car. When she came to know that

he was trying to find a suitable accommodation Masa’ab discussed the matter with

her husband and soon Shuklaji was invited to set up quarters in a room at

Dhanraj Bhavan and have meals with the Parakh family. Shuklaji became a

supporter of Masa’ab’s activities. Through him she came in touch with many

well-known personalities of those days: Dr. Bhagwat from Ratnagiri who taught

her naturopathy, Umashankar Shukla from Wardha, Dada Dharmadhikari and

Thakurdasji Bang who were Gandhian stalwarts. She also met the great socialist

leader Jaiprakash Narayan and attended his meetings.

Refusal

to Enter Politics

Masa’ab notes in her

diary that around 1970 the Chief Minister of Maharashtra Yashwantrao Chavan

visited Chandrapur and she was invited to the meeting along with other members

of the Sarvodaya Mahila Mandal. That night her husband’s friend Uppalwarji

visited them and said that Yashwantrao Chavan wanted to give Masa’ab the ticket

for the upcoming assembly elections. She refused the ticket on the grounds that

she would never be able to support wrongdoings by any party under the garb of

party loyalty – it was better to keep away from politics. Masa'ab's colleague Yashodhara Bajaj went on to win several elections and become a minister.

The Bal Seva Mandir

closed down in 1973 by which time it had provided shelter to around 350

children. She herself had three daughters – Sharadakunwar, Shantakunwar and

Sushilakunwar and adopted a son – Deepak Parekh. It was her intense

desire for a son was fulfilled after meeting the mystic guru Acharya Rajneesh (Osho) in 1960, who declared her as his mother of previous birth.

(Masa’ab’s

meeting with Acharya Rajneesh and later part of her life will be discussed in

the next part.)

- Paromita Goswami

3 Comments

Last week I read some news in news portals that the Acharya Rajneesh has some Chandrapur connection. This article clears the mom of Rajneeshwas was Masa, having deep mighty character.

ReplyDeleteI am also willing to visit the Parakh home to experience the historic happenings. Thanks Kalyanji for giving this morning write-up.

It was my great privilege to have come into close contact with Masaab during my posting at Chandrapur in 1997-98 with Bank of India. Her son Deepak being a very close friend of mine helped me in spending quality time with her not only that one year but in the next two decades too as I regularly visited Chandrapur in connection with the work of Anand Bank the brain child of Sri. Deepak Parakh.

ReplyDeleteInspiring journey. I feel lucky as had the privilege of seeing him in 2015.

ReplyDelete